Introduction

Over the years the word “atheist” has been used in various ways. At one time Christians were called “atheists” by pagans because Christians didn’t believe in their gods. Later, deists like Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine were called “atheists” by Christians. So, for many years, believers have used the word to define those that didn’t believe in their particular god, even if they believed in some other god or concept of god.

Some definitions of the word in the last couple centuries or more may define an atheist as someone who “denies or rejects the existence of God” and/or someone who “believes there is no god,” or variations of these. These definitions were likely formulated by believers and not the atheists themselves.

This explains quotes by people like American writer and professor of biochemistry Isaac Asimov (1920-1992), who seems to have one of those definitions in mind when he said….

“I am an atheist, out and out. It took me a long time to say it. I’ve been an atheist for years and years, but somehow I felt it was intellectually unrespectable to say one was an atheist, because it assumed knowledge that one didn’t have. Somehow, it was better to say one was a humanist or an agnostic. I finally decided that I’m a creature of emotion as well as of reason. Emotionally, I am an atheist. I don’t have the evidence to prove that God doesn’t exist, but I so strongly suspect he doesn’t that I don’t want to waste my time.”

Definitions of this sort are the ones many self-identifying agnostics also seem to have in mind when they resist self-identifying as “atheists.” They correctly think that asserting a claim either for or against the existence of a god without empirical evidence is “intellectually unrespectable.” Some believe these types of definitions puts “atheism” on the same ground as belief, requiring an equal conviction—or “leap of faith”–without knowledge, and frequently leads some to assert that “atheism” is equivalent to religion in that respect. Using definitions like these may also unfortunately result in placing the burden of proof on both sides–theism and atheism–in equal measure.

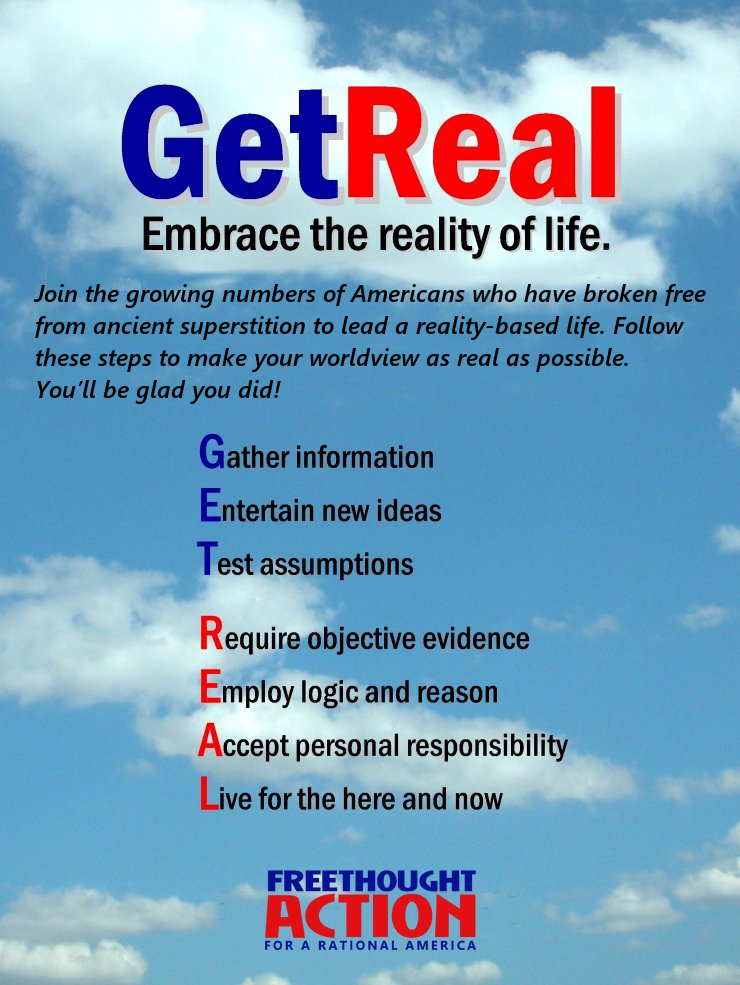

Typing “atheist definition” into Google today comes up with this result: “a person who disbelieves or lacks belief in the existence of God or gods.”

Other online sources that come up near the top of search results include the following:

The Urban Dictionary: “a person who lacks belief in a god or gods.”

Merriam-Webster: “a person who does not believe in the existence of a god or any gods.”

Rational Wiki: “Atheism, from the Greek a-, meaning ‘without’, and theos, meaning ‘god’, is the absence of belief in the existence of gods.”

Wikipedia: “Atheism is, in the broadest sense, the absence of belief in the existence of deities.”

These are more modern definitions of the term.

I submit that the best definition for “atheist” is someone “without a belief in a God or gods,” or as the Oxford Book of Atheism defines it, someone who has “an absence of belief in the existence of a God or gods.”

Here are my 5 main reasons….

#1: Practical Use

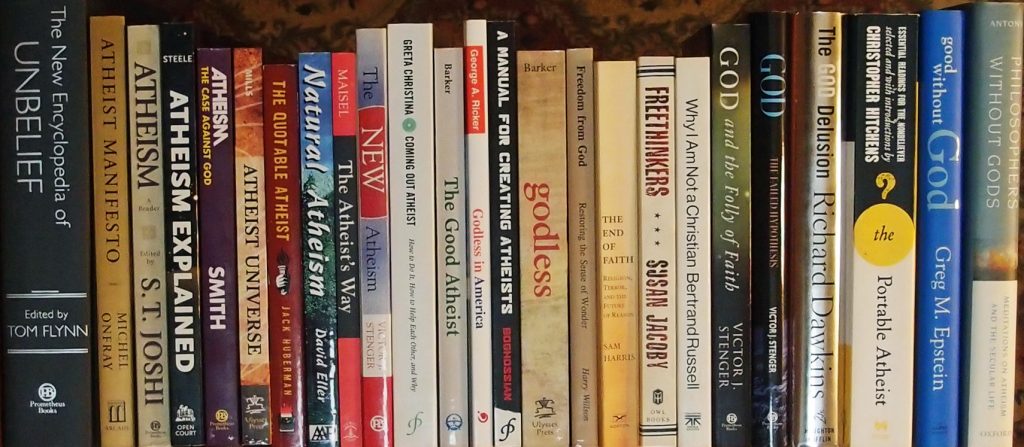

According to their website, “Since 1963, American Atheists has been the premier organization fighting for the civil liberties of atheists and the total, absolute separation of government and religion.” American Atheists is a national organization representing thousands of self-identifying atheists in America.

American Atheists use this definition: “To be clear: Atheism is not a disbelief in gods or a denial of gods; it is a lack of belief in gods.”

Dan Barker is the co-president of the Freedom From Religion Foundation (FFRF), FFRF is the largest national organization advocating for non-theists in the U.S. On page 135 of his book Losing Faith in Faith he says: “Atheism is not a belief. It is the ‘lack of belief’ in god(s).”

Aron Ra is the president of the Atheist Alliance of America, he has said that “A-theism means ‘without theism.’ It is not necessarily a claim of knowledge or even a conclusion. It is simply any perspective that does not include or accept the beliefs held in theism. It is the default position regarding the failure of theists to make an adequate or compelling case for their unsupported and evidently false assertions. Theists know they can’t bear the burden of proof, so they try to reverse it, to shift it onto us, by saying that atheism is a belief that there is no God. No, atheism is a lack of belief in the existence of a god; not the existence of belief in the lack of a god.”

These organizations–American Atheists, FFRF, and Atheist Alliance of America–are the largest membership organizations of this type in the U.S. and they all advocate for a definition that is absent (or without) a belief in a God or gods.

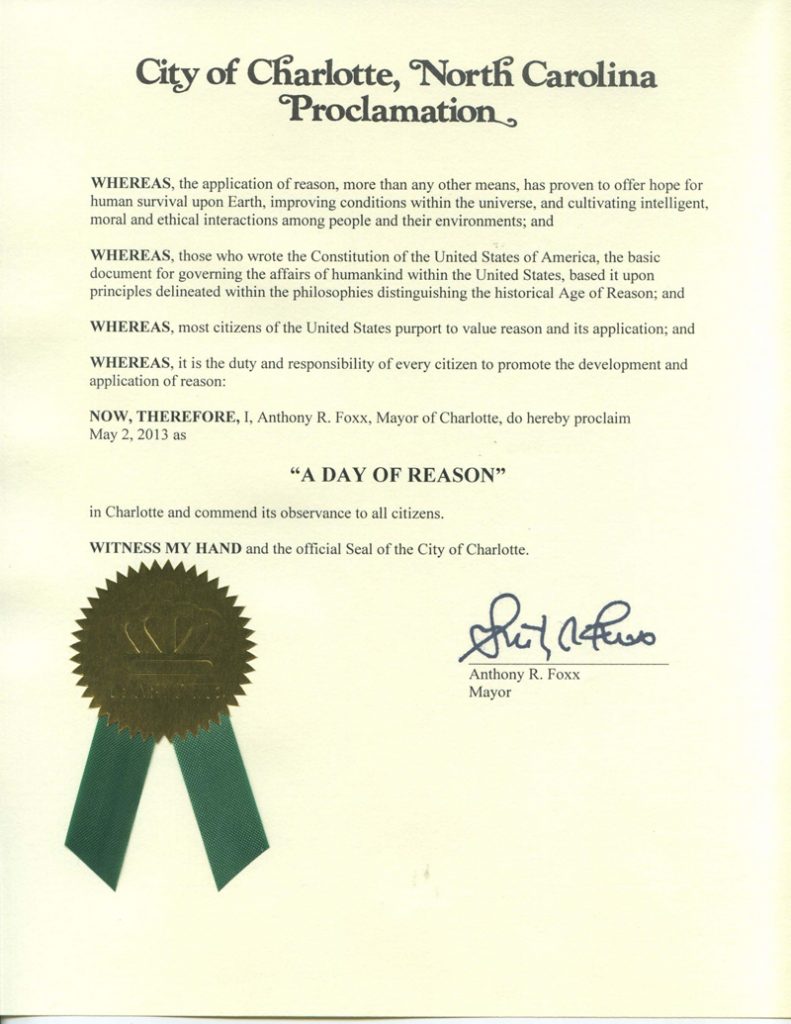

Having been well engaged in the secular/atheist/humanist/freethought movement over the last decade, I can say this definition is typical in local, national, and international nontheist secular organizations.

The American Humanist Association (AHA), for example, touts that one can be “Good Without God.” Roy Speckhardt, executive director of the AHA has said, “By definition, identifying as atheist indicates that one doesn’t have a belief system that includes a god, nothing more.”

From a 2012 Center for Inquiry (CFI) blog post: “Being an atheist doesn’t even mean that you must deny the existence of God. That’s why the proper definition of an atheist includes ‘lacking belief in any god’ and not necessarily also ‘claiming to know no gods exist.’ Reasonable doubt, not epistemic certainty, is enough for an atheist.”

There are other examples, but these are some of the largest nontheist secular membership organizations representing secular nonbelievers in the U.S. that I’m citing. I am not aware of any counter-examples which propose any kind of rejection, denial, or belief that there is no God as definitions of atheism.

Of course, I haven’t surveyed atheists across the world to find out how all of them might define themselves, but it seems we might pay at least some attention to how those organizations who represent them might define it. And it would seem if there were any significant objections from their various memberships, there would be some significant noise about it, which there doesn’t seem to be.

The point is that it might be most relevant to use the definition that people who self-identify by that term would use, especially those organized atheists who are most invested in it. To impose a definition on them from outside would seem to be less accurate in understanding what they actually think.

#2: The Various God Definitions

“God” is certainly a term that is well-known to be used by different people to mean different things. [Note: I won’t be focusing on secondary definitions of the word here (such as: His “god” was money), but more on primary definitions.] Believers of different religions (or faiths) have different concepts in mind when they use this word (although there is some overlapping among some of them, and sometimes different words are used such as “Allah” by Muslims), and different sects within each religion may have somewhat different things in mind when they use the word. It may even be difficult to find two people of the same sect who have exactly the same concept in mind. For this reason, some have suggested that each believer creates “God” in his or her own image, and some charge believers with SPAG (Self Projection As God), but I will pass over that here. Nevertheless, if this is the case, then the term could have a different meaning for each believer.

A review of some selected dictionaries seems to indicate a difference between the use of the word when it is capitalized and when it’s not. For example, Merriam-Webster seems to be providing a definition for the lowercase “god” with its second definition here: “a spirit or being that has great power, strength, knowledge, etc., and that can affect nature and the lives of people : one of various spirits or beings worshipped in some religions,” and Dictionary.com explicitly provides a lowercase definition as “one of several deities, especially a male deity, presiding over some portion of worldly affairs.”

Focusing solely on 1st definitions in these dictionaries and the uppercase use of the word, we find Merriam-Webster defining the term as “the perfect and all-powerful spirit or being that is worshipped especially by Christians, Jews, and Muslims as the one who created and rules the universe.” According to The American Heritage Dictionary, “God” is “a being conceived as the perfect, omnipotent, omniscient originator and ruler of the universe, the principal object of faith and worship in monotheistic religions,” and according to Random House Kernerman Webster’s College Dictionary, “God” is “the creator and ruler of the universe; Supreme Being.” The World English Dictionary defines “God” as “a supernatural being, who is worshipped as the controller of some part of the universe or some aspect of life in the world or is the personification of some force.” Collins English Dictionary defines “God” as “the sole Supreme Being, eternal, spiritual, and transcendent, who is the Creator and ruler of all and is infinite in all attributes; the object of worship in monotheistic religions.” And Dictionary.com defines “God” as “the one Supreme Being, the creator and ruler of the universe.”

According to Wikipedia…

“God is often conceived as the Supreme Being and principal object of faith. In theism, God is the creator and sustainer of the universe. In deism, God is the creator (but not the sustainer) of the universe. In pantheism, God is the universe itself. The concept of God as described by theologians commonly includes the attributes of omniscience (infinite knowledge), omnipotence (unlimited power), omnipresence (present everywhere), omnibenevolence (perfect goodness), divine simplicity, and eternal and necessary existence. Monotheism is the belief in the existence of one God or in the oneness of God. God has also been conceived as being incorporeal (immaterial), a personal being, the source of all moral obligation, and the ‘greatest conceivable existent.'”

Without exploring every last dictionary and encyclopedia available, we can began to gather some idea of how many different believers conceive of the term when it is used in an uppercase sense. “God” seems to be a supernatural and supreme being who created and/or rules the universe. As a result of this “supreme” status, other attributes might or might not include: an eternal and necessary existence, transcendence, perfection, omnipotence, omniscience, omnibenevolence, and omnipresence.

However, as the Wikipedia entry attempts to address, there are some differences between the theistic, deistic, and pantheistic concepts of “God.” If you explore even further, you will find different–and sometimes highly developed–schools of thought about the definition of “God” not only among theists but deists and pantheists as well.

Therefore, it is important to understand what someone means when they use the word in order to understand what they might be claiming or talking about. If the term is undefined, it could mean a very wide range of things. The person using the word may be talking about a personal God who intervenes in the world or they may be talking about an impersonal God who doesn’t. They might have some Eastern concept of God or they might have some Western concept. They might be talking about a Christian God or an Islamic God. They might be talking about “Nature’s God” or even just “Nature,” or they might even be talking about “All That Is” or some ill-defined or undefined “force” or undetectable “energy.”

Muhammad had a different “God” in mind than Martin Luther. John Calvin had a different “God” in mind than Thomas Jefferson. Albert Einstein had a different “God” in mind than Billy Graham, and so on.

It was precisely because Einstein didn’t define what he meant when he used the word “God” at one point that he had to clarify it later because of the confusion it caused….

“It was, of course, a lie what you read about my religious convictions, a lie which is being systematically repeated. I do not believe in a personal God and I have never denied this but have expressed it clearly. If something is in me which can be called religious then it is the unbounded admiration for the structure of the world so far as our science can reveal it.”

In order to understand what anyone means when they use the word, it is important to understand the context or the definition that individual might be using, including the possibility they might be using it only as a metaphor.

So, if we define “atheist” as “someone denying or rejecting the existence of god” or “someone who believes there is no god”–as some persist in doing–we run into the problem of what definition of “god” we are talking about. While I might be able to rule out some definitions as possible (if they are self-contradictory or irrational, for example), I might not be able to rule out all of them. And I certainly can’t rule out every definition any believer might come up with prior to learning what that definition is.

The burden is on the person making the claim to define what they are talking about when they use the word “god.” If they refuse to give a definition, they might as well be using a nonsense word, so what they are talking about is meaningless, and it can be dismissed as such with no reason to even consider it. Until the word is defined, nonbelievers have no way to know what they are talking about, so it would be difficult (if not impossible) to have an opinion on the subject (unless they themselves are assuming their own definition). For example, if the person using the word simply means “nature,” I imagine you would be hard pressed to find an “atheist” who didn’t believe in nature. This is just one example. Some people use the word to mean “All That Is.” If that is what the person using the word really means, then again, you would probably have a hard time finding an atheist who didn’t believe in that (while one might suggest the believer use other words for clarity regarding what they are talking about, we have no control over how people might use the word). I think you will have a difficult time finding an atheist anywhere who is willing to reject the possibility of any and/or every definition of “god” that a believer might come up with.

You might find some who will positively reject some definitions of “god,” perhaps because those definitions are internally self-contradictory or illogical/irrational, which may be fully justifiable, but not every possible definition someone might present. And even if someone thinks they know all possible definitions, new ones are likely to spring up at any moment.

As Gordon Stein pointed out regarding the word “atheism”:

Actually, there is no notion of “denial” in the origin of the word, and the atheist who denies the existence of God is by far the rarest type of atheist — if he exists at all. Rather, the word atheism means to an atheist “lack of belief in the existence of a God or gods.” An atheist is one who does not have a belief in God, or who is without a belief in God. The importance of these distinctions is that one cannot understand what one cannot define accurately. An atheist cannot deny the existence of that which he finds to be without meaning, namely the term *God. In order to deny the existence of something, one must know what the term one is denying means.

Certainly one cannot reject or deny what has yet to be defined. That would be irrational.

#3: Burden of Proof

As I pointed out in the introduction, using definitions for atheist such as someone who “denies or rejects the existence of God” or someone who “believes there is no God” unfortunately puts the same kind of burden of proof on the atheist as it does the theist who believes there is one. The definition “without a belief in a God or gods” avoids that problem entirely.

As a result, this definition is useful in combating the theists’ common assertion that atheism is as much a belief system as theism is, and that it takes just as much “faith” to say there are no gods of any possible definition as it is to say there is one.

It removes the “intellectually unrespectable” issue that Asimov struggled with, as well as the issue that self-identifying agnostics who shun self-identifying as atheists have with it.

#4: Etymology

As Michael Martin (1932-2015) former professor of philosophy at Boston University explains it:

If you look up “atheism” in a dictionary, you will probably find it defined as the belief that there is no God. Certainly many people understand atheism in this way. Yet many atheists do not, and this is not what the term means if one consider it from the point of view of its Greek roots. In Greek “a” means “without” or “not” and “theos” means “god.” From this standpoint an atheist would simply be someone without a belief in God, not necessarily someone who believes that God does not exist. According to its Greek roots, then, atheism is a negative view, characterized by the absence of belief in God.

This would result in treating the definition of “atheism” in the same way we treat other words like “amoral,” “atypical,” and “asymmetrical,” with the “a” meaning “without” or “not,” which would seem to make the most sense.

Here are some other related quotes on the matter, selected because they may be of some interest….

Atheist, in the strict and proper sense of the word, is one who does not believe in the existence of a god, or who owns no being superior to nature. It is compounded of the two terms … signifying without God.

— Richard Watson (1781–1833), British Methodist theologian, author of A Biblical and Theological Dictionary

Etymologically, as well as philosophically, an ATheist is one without God. That is all the “A” before “Theist” really means.

— G.W. Foote (1850-1915), English secularist and journal editor, author of What Is Agnosticism (London, 1902)

The word atheist is a thoroughly honest, unambiguous term. It means one who does not believe in God, and it means neither more nor less.

— Robert Flint, (1838-1910), Scottish theologian and philosopher, author of Agnosticism (Edinburgh, 1903)

If one believes in a god, then one is a Theist. If one does not believe in a god, then one is an A-theist — he is without that belief. The distinction between atheism and theism is entirely, exclusively, that of whether one has or has not a belief in God.

— Chapman Cohen (1868 -1954), English freethinker, atheist, and a secularist, author of Primitive Survivals in Modern Thought (London, 1935)

… the absence of theistic belief …

— Joseph McCabe (1867-1955), English writer and speaker on freethought defining the word atheism in A Rationalist Encyclopedia (1950)

Obviously, if theism is a belief in a God and atheism is a lack of a belief in a God, no third position or middle ground is possible. A person can either believe or not believe in a God.

If theism is the belief in the existence of God, then a-theism ought to mean “not theism” or “without theism.”

— Gordon Stein (1941-1996), American author, physiologist, and activist for atheism, former senior editor of Free Inquiry and the American Rationalist

“Atheist” is quite clear in its meaning of “somebody without a belief in God.” It is more complex in its usage since it has often been used to blacken anyone with the slightest doubt about the teachings of religion.

— Jim Herrick (born 1944), British Humanist and secularist

All children are atheists — they have no idea of God.

— Baron d’Holbach (1723-1789), French Enlightenment philosopher

The man who is unacquainted with theism is an atheist because he does not believe in a god. This category would also include the child with the conceptual capacity to grasp the issues involved, but who is still unaware of those issues. The fact that this child does not believe in god qualifies him as an atheist.

— George H. Smith (born 1949), American author of Atheism: The Case Against God (1974)

Calling Atheism a religion is like calling bald a hair color.

— Don Hirschberg, in a letter to Ann Landers

Atheism is a religion like abstinence is a sex position.

— Bill Maher (born 1956), American comedian, political commentator, and television host

Atheism is a belief system, like “OFF” is a TV Channel.

— Ricky Gervais (born 1961), English comedian, actor, writer, producer

“Atheism is a religion like not collecting stamps is a hobby.”

— Penn Jillette (born 1955), American magician, comedian, author

#5: Inclusiveness

If we accept that an atheist is “someone who is without a belief in a God or gods,” then atheism and agnosticism (or theism and gnosticism) are not mutually exclusive because one has to do with belief and the other has to do with knowledge.

One can be…

An agnostic atheist – one who thinks we can’t know with certainty, but lacks belief.

An agnostic theist – one who thinks we can’t know with certainty, but believes regardless.

A gnostic theist – one who claims to know and believes.

A gnostic atheist – one who claims to know and doesn’t believe.

You will find some who refer to the agnostic atheist position as weak, soft, implicit, negative, or pragmatic atheism and the gnostic atheist position as strong, hard, explicit, positive, or theoretical atheism.

If the “without a belief in a God or gods” definition is used, then not only is it compatible with agnosticism, it also necessarily includes all atheists (weak/soft/implicit/negative/pragmatic/agnostic and strong/hard/explicit/positive/theoretical/gnostic). It becomes an all-inclusive umbrella definition for atheists of all stripes.

Conclusion

Therefore, I submit that the best definition for atheists is “without a belief in a God or gods” or “an absence of belief in the existence of a God or gods” because 1) that is the way I think most organized atheists would define it today, 2) that definition resolves the issue of rejecting in advance something that is yet to be defined, 3) it removes the problematic burden of proof issues, 4) that is the etymology of the word, and 5) that definition makes it compatible with agnosticism and it can include all types of atheists (weak/soft/implicit/negative/pragmatic/agnostic and strong/hard/explicit/positive/theoretical/gnostic).

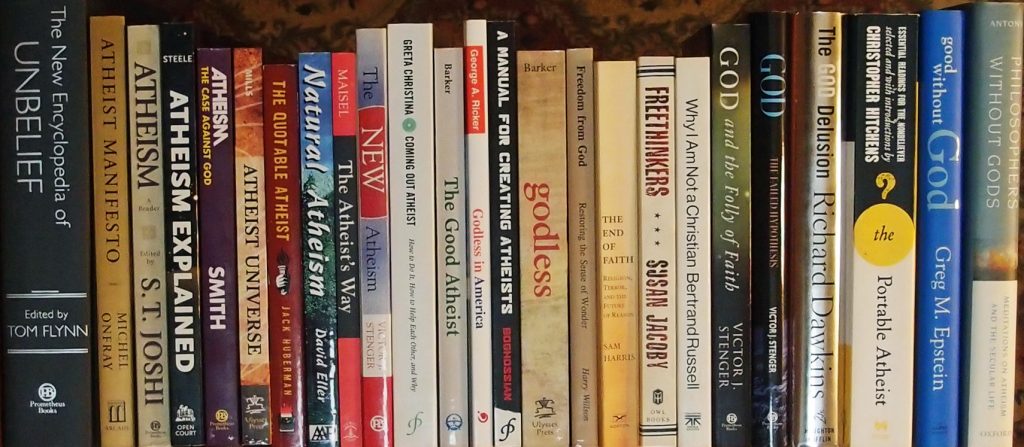

If anyone is interested in going into further detail regarding some of the things I’ve covered above, as well as some reasons that I didn’t cover, I’d suggest reading this excerpt from the Oxford Book of Atheism on “Defining Atheism.” It is a little long, but it is also interesting and informative.

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/friendlyatheist/2014/02/11/defining-atheism-an-excerpt-from-the-oxford-book-of-atheism/

God just spoke to me….

God just spoke to me….